There are considerations other than merely technical ones which have weight in determining the quality and quantity of a man’s work in the shop. For instance, what is distinctly and, pre-eminently the mark of the superior workman? I would unhesitatingly put it as self-respect. The good workman justly appreciates his abilities; and this self appreciation is as far as can be from unwarranted and inordinate self-conceit.

There are considerations other than merely technical ones which have weight in determining the quality and quantity of a man’s work in the shop. For instance, what is distinctly and, pre-eminently the mark of the superior workman? I would unhesitatingly put it as self-respect. The good workman justly appreciates his abilities; and this self appreciation is as far as can be from unwarranted and inordinate self-conceit.

A man in a machine shop, like a man anywhere else in life, who knows how to do good work, knows well enough when he does good work, knows as well as anyone the value of it, and cannot be got to willingly waste it. Work that is wasted is never good work nor done by a good workman. Work may be like choice butter upon good bread, or it may be like the same butter daubed upon the sleeve of your best coat, and then it is not good work.

Troy is the great laundry city—put tight fits upon work that is to encounter the rust of a wash-room, and it will bring you profanity instead of praise. The most worthless man in the shop is he who is willing to swing his axe all day and see no chips fly. The man who is in earnest makes every motion tell to the accomplishment of his purpose. He is the man whom I may always safely tell when anything about his work is wrong. He will know that he is precisely the one who should know about it, that he may correct it and avoid a like mistake in future.

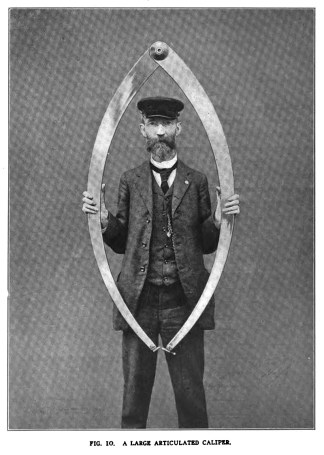

The tool-acquiring instinct is an almost unfailing mark of the good machinist, and the lack of it in a young one is a fatal and hopeless symptom. By the term tools we must cover far more than the rule, square, calipers, and articles of that character. Whatever will facilitate the work entered into may be called tools, all the training of eye and brain, as well as that of the hand, the seeing and thinking which precede the skillful doing, the planning of means and methods in advance of the moment of execution.

Among valuable facilities to a man may be reckoned a knowledge of all the dimensions and movements of the lathe or other machine he operates. I have seen a man who has run a certain planer for ten years, and who does not to this day know how far a turn of the crank will raise his cross-head, and when making a change he usually has to stop and apply his rule two or three times before he gets to the right height. Another has to run a drill a certain distance into a piece that he has in his lathe chuck, and to make sure, he gets a file and cuts a notch in the drill, instead of knowing the pitch of the tail screw and counting the turns of it, which would do the work with greater accuracy.

I verily believe that I am disposed to be kind and helpful, and am not lacking in patience, but I have very little of it to waste upon the fellow “learning the trade” who expects to be told every detail of it. He wont have the trade learnt in a hundred years. Only a week or two ago I scolded as sharply as I knew how a young man who has been in the shop three years, and who did not know how to adjust the stroke of a shaper. “Nobody ever showed him how;” why, nobody ever showed me how, and he had as good facilities for learning the matter as I had. I mention this with impunity, as he is not one of those who read the American Machinist.

The trade becomes continually less and less manual. There is less pushing the file and swinging the hammer. Muscle is at a discount and brains are far above par. One who expects to become a machinist without mental training had better step out. One is never learning anything unless he is in trouble. If I got hold of a bright and ambitious young man and wanted to push him, I would keep him in hot water all the time. There is a power of virtue in hot water.

Akin to the tool-acquiring is the tool preserving instinct, of which I want to speak more fully than I can at the end of this. It is a great point to have tools always in order, always in place and in a handy place, everything not wanted out of the way, and ones surroundings roomy and comfortable. We rise by opportunities, and they are few and far apart, and he whom the opportunity finds equipped and alert is the one to mount and master it.

Frank H. Richards

American Machinist – February 3, 1883

– Jeff Burks