In attempting to prove that the minute subdivision of labor has an evil tendency, I am aware that I shall meet with few who will admit the evil to be so extensive as I shall endeavor to point out; and it is very probable I shall be written down by some of the many able correspondents of the Mechanics’ Magazine.

But as the following facts are the results of long observation and experience among the working classes, I have resolved to publish them anonymously, in the hope that they will meet the eye of some who may be benefited by them; and should they be the means of convincing even one, I shall consider myself happy in having brought the subject into notice. I have myself served an apprenticeship to a mechanical profession, and had then ample opportunities of observing the causes that tend to bring about the moral degradation of some of the working classes.

That the division of labor produces a cheaper article, and is a great source of national wealth, I readily admit. I believe were it not for this very cause, Britain would ere this have lost her political status among the nations. Groaning under a load of taxation, which no other nation on earth could have borne, we have been driven into an artificial state of society, and the division of labor with all its attendant evils is one of the results.

This is illustrated by the fact that we export machinery to countries where workers are obtained at half the price: and yet these countries are unsuccessful competitors in the same market with the poor tax-eaten British. Our national vanity whispers that this is owing to our superior genius; but I contend that it is our artificial mind-degrading system of dividing labor, which by making individuals do only one part of a thing; with mechanical, or rather slight-of-hand, rapidity, enables us to produce a whole as cheap as our foreign brethren.

But the effects of this system upon society is truly deplorable. A poor boy, with very little education, is bound an apprentice for five or seven years, to do one particular act; he commences cheerfully, and in a few weeks can manage it completely; the only difference between him and a journeyman being that he takes twice the time.

He is now doomed through life to be a mere machine; all the delight he felt in learning his trade is over; he has no more mental work to perform, and he goes on from day to day with his monotonous task without excitement of any kind, save the temporary one of the gin-shop: there, amongst the rudest ribaldry and mirth, he is exhilarated and comparatively happy. Next day he returns to his labor in the most melancholy and discontented mood, and hastens on with his work to procure the means for “a hair of the dog that bit him.”

In short, as his profession does not exercise his intellect at all, he cannot fail to indulge in what he thinks his only pleasure. Let us suppose this to be continued until he reaches man’s years, when the effect will be seen in an intellect, blunted, and quite useless from inaction. For we know well, that the thinking, like the physical, part of the man, is either perfectly or imperfectly developed—by proper or improper exercise. This man’s brain is unexercised, nay, it is diseased; he has acquired a sensual and ungovernable appetite for the drug that enfeebled, and still continues to enfeeble, both his mind and body, and he is in such a morbid state, that all his efforts to reform or improve his mind are ineffectual.

He tries Mechanics’ Institutions, and all the other schemes for improving the working classes, but to no purpose; his mind, from want of habit, cannot follow the lecturer; he gets inattentive—sleeps—and loses the thread of the subject; repeats his visits for a night or two, perhaps, and the lectures get to him “the longer the drier,” until he quits in disgust, what might, under other circumstances, have been a source of enjoyment to him.

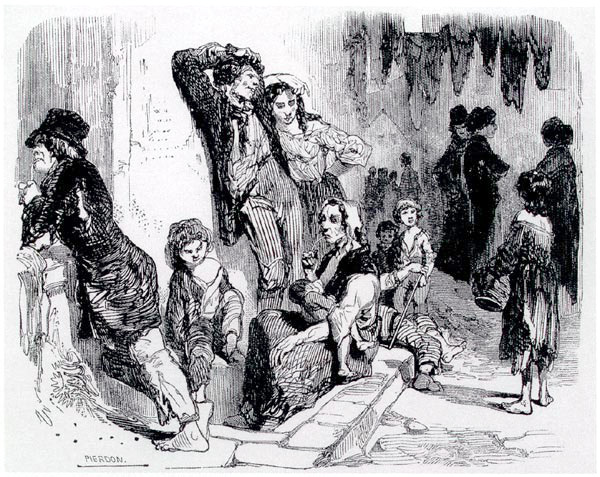

When such a character enters into the solemn engagements of matrimony, his previous habits and badly regulated mind ill qualify him for the various duties of husband or father; he brings into the world a few squalid, degenerated wretches, and by his brutal conduct, drives his well-disposed partner to that temple of infamy the gin-shop, for the melancholy purpose of “drowning her cares.” I will not disgust the reader by dwelling upon the united effects of their example on their thus hereditarily vicious offspring.

The wretched man continues to work and drink alternately, until he reaches the workhouse if in England, and beggary and crime if in Scotland: a poor grumbling, discontented, shameless pauper, both unable and unwilling to work; for the man who has spent twenty years of his life sharpening pinpoints, or guiding a self-acting turning machine, has not physical strength to handle a spade or road hammer, even if he had not been previously wasted by dissipation.

This is not an exaggerated picture; the melancholy details of evidence brought before the Factory Commission furnish multitudes of such instances. It is not the long hours, however, that is the sole cause of this evil I maintain: it is the division of labor that is the root of the evil, which I shall endeavor to illustrate by another example, not ideal, but like the former, real: and the writer has many characters under his own eye, of both kinds, to choose from.

In Scotland, some ten or twelve years ago, the division of labor was not (and is not even now) carried to the extent that it is in England, and consequently the working classes have a higher moral character, which is commonly ascribed to education, and a modern training. This is the case in a very few instances; by far the greater number of the Scotch mechanics and operatives receive a very limited education. When they are sent off to a trade, they can half read, and perhaps make shift to write the letters of their own name—but the difference rests here; the Scotch mechanic has to do a great variety of jobs, not one of which he can do so quickly as the expert Englishman.

As an instance: About twelve or fourteen years ago, an engine-maker had to learn to make a tolerable good pattern; he had to turn both iron and wood, to fit up, put together, and attach the engine to the factory; he had thoroughly to understand drawings, and in many cases had to draw himself. The reader will readily imagine, that this must be a clumsy “Jack of all trades:” this is not the case however,—he is a slow, but a good workman.

Suppose exactly such a boy as we took in the former case, bound apprentice to this trade for seven years: for one year he is allowed to run loose about the work, he is every “body’s body,” runs messages, creeps into holes to do jobs which men cannot reach. By the end of the year, he has acquired a very rude general notion of the whole work, but can do little or nothing with his hands.

He is now stationed at a bench, and from making simple articles, comes on with great satisfaction to himself to make good patterns; he then wearies, because he thinks himself master of the subject; having little mental work to perform, he is now in great danger of going astray, but happily for himself he is shifted to another department, upon which he enters with great spirit, and feels with intense delight, as bit by bit he masters the various tasks put before him. His brain thus stimulated and exercised, a thirst for knowledge is created, and he is driven in search of food for his mind to a Mechanics’ Institution, where he hears and sees, for the first time, the astonishing fact, that the water he drinks is composed of two gases that burn.

This leads him to endeavor to read, that he may learn more of the matter, but he finds he cannot do it so quickly as he would like; he then sets to work with good will, goes to an evening-school, and his mind being in an excellent state for receiving instruction, he makes most rapid progress. I need not trace him farther—here is a useful and promising member of society, who himself enjoys life and all its blessings.

A few such (according to the strength of their intellect) turn out eminent men—the rest are scattered over the earth in the shape of managers, superintendents, and foremen of flourishing works; and it is worthy of remark, that in all the large manufacturing towns in England you find a large proportion of Scotchmen doing the intellectual work of large mechanical establishments. This does not arise (as Sandy’s vanity always suggests) from a “national superiority.” John’s head is just as good as his, as is seen in every case where there has been the same chance of getting the organs developed.

I regret to state that the baneful system of dividing labor is fast spreading in Scotland, and the moral degradation attending it cannot be denied by the most ardent admirers of the religion and morality of that country. It must not be supposed that the character I have last attempted to describe has been exempt from temptation. No, he has kept company with the drunken and the dissolute (of which there must be a large proportion in every society;) but his mind having been properly set to work, he soon calculated the amount of real pleasure or pain to be derived from seeking after knowledge, or from a course of profligacy.

Nor must I be understood as assuming that all are depraved who labor at one particular object all their lives, for there are some minds that naturally resist the influence of such causes; but the number of the good bears a small proportion to the bad in countries where this vicious system is carried to great extent. There is another demoralising effect yet to be noticed, which I shall endeavor to do as briefly as possible.

An improvement in machinery often turns hundreds adrift upon society, who having spent the best part of their lives in some such trifling work as heading pins, are too old to learn another business, and for reasons already mentioned they cannot do out-door work; their minds being untutored, they do not make a very vigorous effort to do their best at a new job, well knowing that they will not be allowed to starve in England.

In many, very many cases, such men direct their blind rage to the breaking of machinery, not only the machine which superseded them, but machinery of all kinds; in short, a large proportion of the seditious, the incendiaries, the swings, machine-breakers, &c. which disturb the peace of society, are division-of-labor people, thrown out of work, and who have neither physical nor mental strength left to turn themselves to another decent employment, seeing that the few that do so are scarcely fit to earn sufficient to support a miserable existence.

It is common enough to hear the lordly aristocrat, or wealthy man of business, express their disgust in such unmeasured terms, as the “beastly multitude,” the “canaille,” the “scum of the earth,” &c., and grumble loudly at the overwhelming poor-rates. Let them examine themselves carefully, and see that they be not aiders and abettors of such infamy. Let them remember, that the cause of this evil is overtaxation (and every one who directly, or indirectly, robs the public purse, is to blame for perpetuating the evil,) and not turn away in disgust from his fellow-being whom he has already injured.

We take some trouble to educate the lower animals, and if some of these our humble servants are not so tractable as could be wished, we do not vent our anger upon them, but upon their trainers. Why, then, should the higher classes spurn the poor, misled, untrained mechanic, whose labor has perhaps enriched them?

It were a wiser course, and a way to root out the evil, were they to set on foot a proper plan of national education, inquire into, and amend, some of the absurd apprentice-laws, and put the rising generation in the way of acquiring more than one branch of a business, in order that their minds may be so far exercised as to make them good members of society, instead of converting them into mere machines for the acquisition of wealth.

We see the good effects produced in the middle classes by education. Why, then, should a large proportion of our fellow-creatures be allowed, or rather doomed, to remain in a state of darkness? I trust these remarks will be followed out by some of your abler correspondents at some future period. I am afraid I have already occupied too much of your valuable space.

L. May 4, 1835.

Mechanics’ Magazine – (London) Saturday, June 13, 1835

—Jeff Burks