I am going to tell you about a little boy who had scarlet fever, and about how he amused himself. He was quarantined in his own room for six weeks, yet he did not have a dull time, after all. He saw no one during those weeks but his father and mother and the doctor.

When Arthur was first taken sick and the doctor said that it was scarlet fever, every unnecessary article of furniture was removed from his room. His bed seemed very necessary, so that remained; also his bureau, washstand, a table, and two chairs. The carpet was taken away, as well as the book-case and all the books. The closet was emptied of all the clothes, and the drawers full of toys were stowed away in the attic.

When so many of his cherished belongings were gone Arthur thought it was a very queer-looking room, and the first time he sat up in bed and looked at the bare floor he said it seemed as if he were in prison.

In a week he was able to be up and dressed, and in a few days more he began to feel so well that he asked what he could do to amuse himself. His playthings were gone and his books. What could he do, sure enough? His mother, too, began to wonder. The doctor said he must not go down-stairs, or even leave the room, for six weeks from the beginning of his illness. Ten days were gone, but what should be done with the thirty-two remaining?

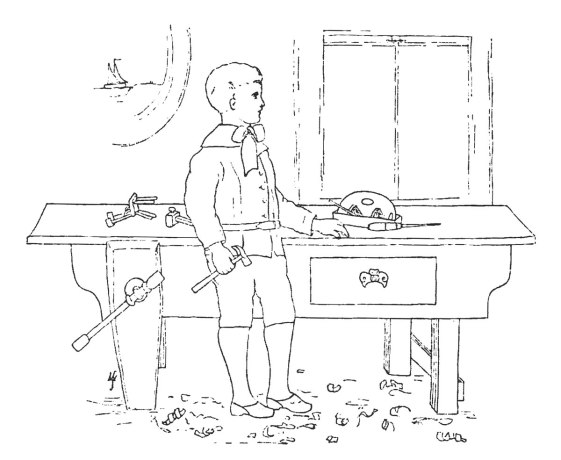

Arthur’s father made a happy suggestion. He proposed that Arthur should have his work-bench brought from the barn up-stairs to his room, and then, with his tools and a supply of sticks and blocks of wood, he might work away to his heart’s content. There was a great deal of measuring to find out whether the bench was small enough to go through doors and up stairways, and the next morning the question was settled.

The neighbors, if they were looking out of their windows, must have seen a funny sight. The work-bench, six feet long, was carried around the house, the double front doors were thrown wide open, and the bench disappeared through the vestibule. Up the front stairs it went, through a long hall, and into Arthur’s room,—the service worn old bench, never more prized than now when it had so important a part to play in the family history.

Now that Arthur was going to be a little carpenter, how convenient it was to have a bare floor in his room! The strips and pieces of wood of all sizes, brought from the carpenter’s shop, were piled upon the floor under the work-table. The drawers were opened, and out came all the tools,—the plane, the brace and bits, the draw-knife, saw, and hammer.

Arthur’s eyes fairly shone as he greeted one by one his familiar friends. Here a difficulty arose. There was a work-bench, there were the tools and the wood, and there was the boy himself,— the little workman. But what should he make first? He asked his mother.

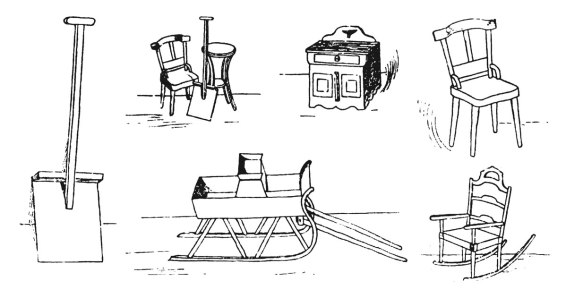

“Suppose you try to make a chair,” was her reply. Arthur looked somewhat doubtful as he said, ” I never made anything of that sort in my life.” But he worked away all one morning, and succeeded in making a chair of simple design.

A little friend of Arthur’s has drawn a picture of the chair for you to see; and the same little girl drew all of the pictures in this story directly from the objects themselves.

The next day Arthur was in a hurry to be up and dressed, so as to make all sorts of things which were taking shape in his boyish mind.

Day after day Arthur worked happily on with his tools. Sometimes his mother read to him while he worked. He did not wish bound books taken to his room for fear they would have to be burned when he was well. But single numbers of the St. Nicholas, which could be replaced, and copies of other magazines and papers found their way in and were very welcome.

About four o’clock every afternoon Arthur began to put his room in order. He put the tools back into the table-drawers, and swept up the chips and shavings which had gathered during the day. Then, every day or two these were carried away and carefully burned. Each day a new piece of furniture was added to the row of dainty designs on the bureau. Arthur asked to have them placed so that he could see them all when he first waked in the morning.

Sometimes the hour just before it was time to light the lamp, and after the work was over for the day, seemed rather long. So Arthur’s mother proposed that they should play “Thirty-one,” looking out of the window. From the east window they could look a long distance up a busy street, and all the people who came down the right-hand side of the street Arthur counted for his side, and his mother counted all who came down the left side of the street on her score. Whoever first counted thirty-one passers-by on the chosen side of the street won the game. They played this many times every afternoon until it grew too dark to see the people.

After the first week of his illness Arthur did not need to have his mother sleep in the room with him, so she would tuck him in very comfortably about eight o’clock every night, and leave him with a stout cane by his bedside to knock on the wall if he wished to call her during the night, for she slept in the next room. As he waked very early every morning, the time seemed long until his mother could come to him and attend to his rising and dressing himself.

He was also very hungry, so his mother covered over in a saucer by his bed one cracker and, as a special treat, one marsh-mallow for him to eat every morning. After a while these were not enough for his early morning diversion, so his mother suggested that he should compose a nonsense verse to repeat to her when she came in to bid him good-morning. Here is the verse he had all ready to recite to her the first morning:

There was an old fellow of Bute,

Who thought he could play the flute;

When they asked, “Play a tune?”

He replied, “You’re too soon;

Come over this eve, and I’ll toot!”

After that he never found the time long before his mother’s early visit, as the verse-making, in addition to the cracker and the marsh-mallow, furnished abundant occupation.

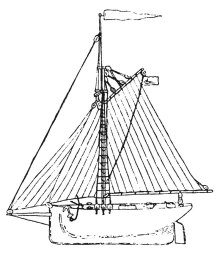

When four weeks had gone, Arthur’s interests in making furniture was at a low ebb. Then he thought he should like to make a boat. So his father brought him a solid piece of wood of just the size he needed, six inches through each way by fifteen inches long, and he began work again with fresh enthusiasm. It took him one week to shape and hollow the hull and put on the deck. Next came the masts, and then all the rigging.

What a busy time it was! He worked very fast, for the day was approaching when he could be released from his imprisonment, and he hoped to finish the boat before he left his room. And so he did, all but a few very last touches, which were added some weeks later. The boat was named the “Altama,” after a beautiful yacht owned by a gentleman living near Boston. This gentleman had kindly given Arthur a sail in Boston harbor the summer before, when he went with his mother to the seashore.

When the six weeks were over Arthur went out of his room a very happy-looking rosy boy, because his body and mind had been kept occupied, and he does not think it is so very bad, after all, to have the scarlet fever—as he had it.

Sara Wyer Farwell

St. Nicholas: An Illustrated Magazine for Young Folks – 1889

—Jeff Burks