A business man, speaking of one of the most pushing and active men in his employ said to me recently, “He does a lot of work but spoils much of it. He will work like a tiger to get a lot of things done, to make a record in output, but he botches so many things that the net result of his work is not nearly so effective as is that of others who do not make half the splurge, the push and noise that he makes.

Now to have to do a lot of work in order to make a big show does not amount to anything. Lack of thoroughness, of completeness, makes it worse than useless. People who make a splurge, young men with spasmodic enthusiasm, spasmodic effort however great, however spectacular, do not get the confidence of level-headed men.

It is the man who does everything he undertakes just as well as it can be done; who takes a pride in putting the hallmark of excellence upon everything that passes through his hands; the man who does not have to do his work over and over again, but who starts well and does everything to a finish, who is quiet, energetic and industrious, this is the sort of a man that comes out best in the end.

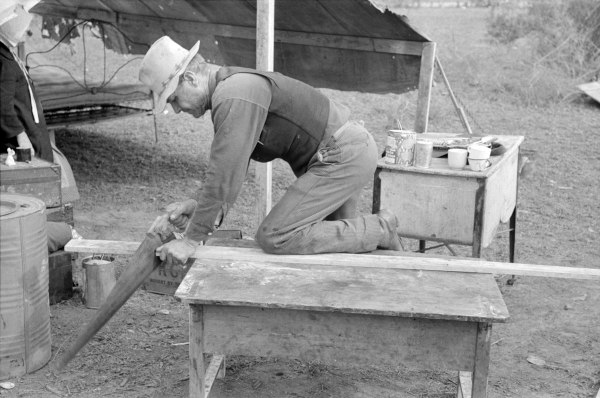

I once knew a carpenter who was engaged to do a cheap job for a customer, who told him distinctly that he was not to put good work into it, because he didn’t want to pay much for it. When the customer returned home he was surprised to find that the carpenter had done a superb job, just as though it was to be seen by everybody instead of being in an out-of-the-way place, where cheaper work would have answered just as well.

He expressed his surprise when the carpenter asked only a very small sum for his work. “But,” said the carpenter, “you didn’t expect to have to pay me for doing the kind of a job I have done, and I don’t expect to be paid for it. The extra effort and time I put into the work for the effect upon myself. I couldn’t afford to demoralize myself by doing a poor job.”

Is it any wonder that when other carpenters are hunting a job, this man has more jobs than he can do? Apart from the fact that doing his work in a superb way makes a man an artist and largely increases his earning power, there is nothing else quite like the satisfaction that comes to one from the consciousness of doing the very best thing possible to him.

What a sense of well being we experience after we have done a superb day’s work, when we have shown ourselves to be the master in every detail of the day, when we are conscious that we have been artists instead of artisans in everything we have touched. What a glow of happiness fills our very being when we feel that we have lived a masterful day, that we have not played at life, that through the high quality of work we’ve put into it the day has been a red-letter day in our lives, a mile-post in our career.

On the other hand, when we have done a poor day’s work, when things have been at sixes and sevens, because we dawdled or idled, when our efforts have been weak, ineffective, unscientific, inefficient, when we have done our work in a slovenly, slipshod way, or at best in an indifferent, half-hearted way, we have a feeling of condemnation, of humiliation, of disappointment, of regret.

We are dissatisfied, disgusted with ourselves because we have used the magnificent machinery at our command during the day to turn out poor work, a botched job. We know we have made a daub of what we might have made a masterpiece, and this is hell enough—to feel that we have accepted inferiority from ourselves when we should have demanded superiority.

If you are not humiliated by a poorly done job, an indifferent day’s work; if you are satisfied with the botched and slovenly; if you are not particular about quality in your work, in your environment, in your personal habits, then you must expect to take a second or third rate place, to fall back into the rear of life’s procession.

I know a writer for a newspaper and cheap periodicals who tells me that he is nothing but a hackwriter anyway, that he doesn’t pretend to be anything else; he says he is just trying to make any sort of a living, and is not concerned about the accuracy or quality of the stuff he turns out so long as he gets paid for it. He doesn’t seem to know what it is to take pride in his work or what it means to demoralize himself by putting only his second-best into it.

There is nothing ahead of this young man but failure, for it is only by the perpetual effort to stamp superiority upon everything we do, to put the hallmark of our character upon everything that passes through out hands, to do our level best under all circumstances, that brings the best out of us; that calls out the larger man, the more glorious man.

The chances are, my friend, that you don’t know the A, B, C of the possibilities of the very position you are complaining about. The employer, who you think is not fair with you and does not appreciate you, may be watching you right now and regretting the fact that you cannot see your chance, that you are not making the most of your opportunity. He may see that you are getting into a rut, that you are not taking an interest in your work, that you are not putting your best into it, and everything depends upon the impression you are making upon your employer.

“I’ll tell you how I got on” said a young man who was recently questioned about his rapid promotion, “I kept my eyes open and my ears open. I considered myself a real partner in the business, and I did what I thought my employer would do if he were in my place. I always made his interests my own, and thought of the business as my own. If I saw a waste going on anywhere I tried to stop it. If I saw other employes botching their work, or spoiling merchandise, I felt it my duty to try tactfully to induce them to do better. It seemed to me that it was just as dishonest to steal my employer’s time, to waste or spoil his goods, as to steal his money.

I did not realize that my employer was watching me. I did those things simply because they were right, but it seemed that he had had his eye on me for a long time before he finally called me into his office and told me that I was to be promoted. The other employes said that my promotion was due to favoritism; that my employer liked me personally and that was all that was to it. But I knew better, and so did my boss.”

No matter what you do, try to be a king in your line. Have nothing to do with the inferior. Do your best in everything; deal with the best; choose the best; live up to your best. If there is that in your nature which will take nothing less than your best in everything you do, you will achieve distinction in some line if you have the persistence and determination to follow your ideal.

People who have accomplished work worth while have set a very high standard for themselves. They have not been content with mediocrity. They have not confined themselves to the beaten tracks; they have never been satisfied to do things just as others do them, but always a little better.

Whatever you do in life do it with the same zeal, the same enthusiasm, the same thoroughness which Stradivarius put into the making of his violins, which today are worth thousands of dollars apiece. The master violin maker needed no patent, no trademark on his violin, his name was enough. “Stradivarius” marked on a violin meant that it was the best violin that could be made. It meant a degree of excellence which no other violin maker had ever attained. Make it a life rule to stamp your best upon everything that goes through your hands. Be just as proud of the product of your endeavor as are the celebrated men who have made world-wide reputations from the excellence and superiority of their product.

It is said that Leonardo di Vinci, after a hard day’s work, would walk clear across the city, to deepen or lighten a shade which he thought would improve his immortal frescoes. It is just the little touches after the ordinary artist would stop that makes the master artist’s fame. The same is true with the actor, the singer, the sculptor, with everybody who has become an artist in his or her specialty.

If you are able to say of yourself of every job you put out of your hands, “There, I am willing to stand for that piece of work; it is not fairly well done, pretty well done, but it is done just as well as I can do it, done to a complete finish; I am willing to be judged by it; I am willing to have everybody know that I did that job. I have put my hallmark the trade-mark of excellence upon it”—there is no fear but that you will be a marked man or a marked woman in your specialty.

Orison Swett Marden

The Business Philosopher, and Both Sides – June, 1919

—Jeff Burks